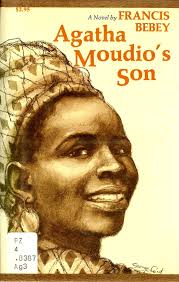

Below is ‘Ma vie est une chanson‘ or ‘My Life is a Song‘, a love poem by Cameroonian author Francis Bebey, a poem celebrating his love for the African woman, in this case for his lover. As we remember that Francis Bebey was multi-talented as a journalist, writer, sculptor and musician, it is no surprise that the title of his poem is “My Life is a Song”. He even headed the UNESCO music department researching and documenting traditional African music. In the poem, he highlights that he was born from the love of the earth with the sun, thus a birth that was very celebrated and a life full of love. As we read the poem, Bebey’s love for his country is abundantly clear as he dreams of taking his lover there, and not only that, but lets her know that his country is where to find the love between the earth and the sun; it is almost as if he was telling all that he was born on the equator. Moreover, let’s face it, the link between the earth and the sun is undeniable, unbreakable, unavoidable, constant, and forever omnipresent. He is so taken by the love so much so that his life is a song that he will sing everyday to his precious one. Wouldn’t you all like to be loved like that? Enjoy!

Below is ‘Ma vie est une chanson‘ or ‘My Life is a Song‘, a love poem by Cameroonian author Francis Bebey, a poem celebrating his love for the African woman, in this case for his lover. As we remember that Francis Bebey was multi-talented as a journalist, writer, sculptor and musician, it is no surprise that the title of his poem is “My Life is a Song”. He even headed the UNESCO music department researching and documenting traditional African music. In the poem, he highlights that he was born from the love of the earth with the sun, thus a birth that was very celebrated and a life full of love. As we read the poem, Bebey’s love for his country is abundantly clear as he dreams of taking his lover there, and not only that, but lets her know that his country is where to find the love between the earth and the sun; it is almost as if he was telling all that he was born on the equator. Moreover, let’s face it, the link between the earth and the sun is undeniable, unbreakable, unavoidable, constant, and forever omnipresent. He is so taken by the love so much so that his life is a song that he will sing everyday to his precious one. Wouldn’t you all like to be loved like that? Enjoy!

The poem ‘Ma vie est une chanson‘ by Francis Bebey, was published in Anthologie africaine: poésie, Jacques Chevrier, Collection Monde Noir Poche, Hatier 1988. Translated to English by Dr. Y. Afrolegends.com.

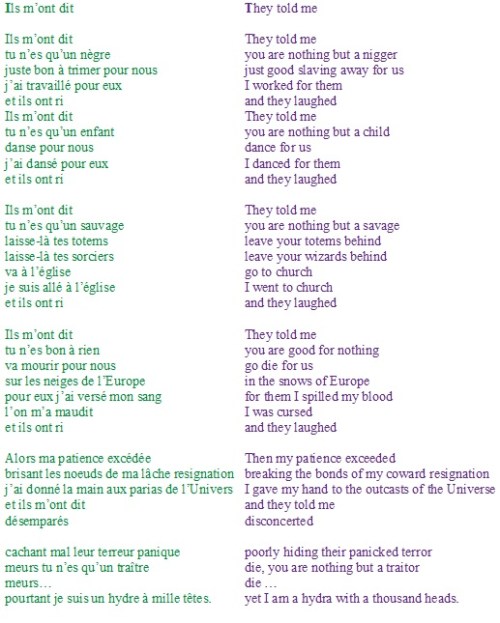

| Ma vie est une chansonOn me demande parfois d’où je viens

Et je reponds “je n’en sais rien Depuis longtemps je suis sur le chemin Qui me conduit jusqu’ici Mais je sais que je suis né de l’amour De la terre avec le soleil” Toute ma vie est une chanson Que je chante pour dire combien je t’aime Toute ma vie est une chanson Que je fredonne auprès de toi Ce soir il a plu, la route est mouillée Mais je veux rester près de toi Et t’emmener au pays d’où je viens Ou j’ai caché mon secret Et toi aussi tu naîtras de l’amour de la terre avec le soleil Toute ma vie est une chanson Que je chante pour dire combien je t’aime Toute ma vie est une chanson Que je fredonne auprès de toi. |

My Life is a SongI am sometimes asked where I come from

And I answer “I don’t know For a long time I have been on the way That leads me here But I know that I was born from the love between the land and the sun” My whole life is a song That I sing to tell you how much I love you My whole life is a song That I hum next to you Tonight it has rained, the road is wet But I want to stay close to you And take you to the land where I come from Where I hid my secret And you too will be born from the love of the earth with the sun My whole life is a song That I sing to tell you how much I love you My whole life is a song That I hum next to you. |

In these uncertain times, I thought about sharing with you this poem by the Cameroonian author Etienne Noumé, ‘

In these uncertain times, I thought about sharing with you this poem by the Cameroonian author Etienne Noumé, ‘