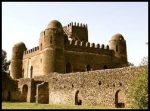

I am going to start a series on reclaiming our history. I will be talking about slave forts across Africa. There were over 30 slave forts in Ghana only. How many in other countries? We will find out through this exercise. These fortified trading posts were built between 1482 and early 1800s by Portuguese, British, Swedish, English, Danish, Dutch, and French traders that plied the African coast. Initially, they had come in search of gold (in Ghana), ivory (in Ivory Coast), pepper (along the Pepper Coast) and then later, they discovered cheap labor: thus was born the slave trade. There was intense rivalry between those European powers for the control of the West African coast from Senegal, to as far south as Angola.

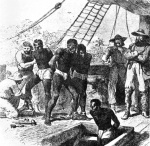

It is estimated that over 20 million Africans were sold into slavery during the Atlantic slave trade; this does not account for those who died during the trip aboard the ship (about 1/3), and those who were killed during the capture. Slaves were taken to North America, the Caribbeans, and Brazil. Moreover, this is an estimate for the transatlantic slave trade only, but did you know that slaves were also taken by Arabic sailors from the East Coast of Africa, to places like Saudi Arabia and as far as India?

The Portuguese began dealing in black slaves from Africa in the 15th century. Initially, they purchased slaves from Islamic traders, who had established inland trading routes to the sub-Sahara region. Later, as the Portuguese explored the coast of Africa, they came upon the Senegal River, and found that they could purchase slaves directly from Africans. The European slave trading activity moved south along the African coast over time, as far south as Angola. On the east coast of Africa and in the Indian Ocean region, slaves were also taken from Mozambique, Zanzibar and Madagascar. Many of the slaves were from the interior of Africa, having been taken captive as a result of tribal wars, or else having been kidnapped by black slave traders engaged in the business of trading slaves for European goods. These slaves would be marched to the coast to be sold, sometimes traveling hundreds of miles. Many perished along the way. The captured Africans were held in forts or slave castles along the coast. They remained there for months crammed in horrible conditions inside dungeons for months before being shipped on board European merchant ships chained at the wrists and legs with irons, to North America, Brazil, and the West Indies.

Some African rulers were instrumental in the slave trade, as they exchanged prisoners of war (rarely their own people) for firearms which in turn allowed them to expand their territories. The slave trade had a profound effect on the economy and politics of Africa, leading in many cases to an increase in tension and violence, as many kingdoms were expanding.

The slave trade was responsible for major disruption to the people of Africa. Women and men were taken young, in their most productive years, thus damaging African economies. The physical experience of slavery was painful, traumatic and long-lasting. We know this from the written evidence of several freed slaves. Captivity marked the beginning of a dehumanizing process that affected European attitudes towards African people. Can you imagine losing 1/3 or more of your active population? It is hard to fathom what crippling effect that will have on any country’s progress. That is why, in upcoming months, I will be talking and trying to identify slave forts in Africa, in an attempt to reclaim our history. I know this is a touchy subject, but it is history: the bad, the ugly, the beautiful, the joyous. It is important to know history in order to be able to claim the future fully, without any baggage.