Today, I will be talking about Idris Alooma (also Idris Alaoma, or Idris Alauma), the only Bornu King whose name has survived the test of time. This article is long overdue, as it focuses on the Bornu and Kanem-Bornu empires.

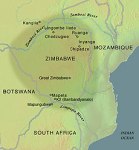

Idris Alooma’s reign belonged to the great Sayfawa or Sefuwa dynasty which ruled the Bornu empire from the 16th and 17th centuries. According to the Diwan al-salatin Bornu, Idris Alaoma was the 54th King of the Sefawa dynasty, and ruled the Kanem-Bornu empire located in modern-day Chad, Cameroon and Nigeria. In many works, he is known by his mother’s name, Idris Amsami, i.e. Idris, son of Amsa. The name Alooma is a posthumous qualificative, named after a place, Alo or Alao, where he was buried. He was crowned king at the age of 25-26. According to the Diwan, he ruled from 1564 to 1596. He died during a battle in the Baguirmi where he was mortally wounded; he was later buried in Lake Alo, south of the actual Maiduguri, thus the name Alooma.

Idris was an outstanding statesman, and under his rule, the Kanem-Bornu touched the zenith of its power. He is remembered for his military skills, administrative reforms and Islamic piety. His feats are mainly known through his chronicler Ahmad bin Fartuwa. During his reign, Idris avoided the capital Ngazargamu, preferring to set his palace 5 km away, near the Yo river (Komadugu Yobe), in a place named Gambaru. The walls of the city were red, leading to a new architecture using red bricks characteristic of his reign. To this day, some murals still exist in Gambaru and are over 3m tall. These are vestiges of a flourishing empire. Idris Alooma was known by the Kanuri title of Mai for king.

His main adversaries were the Hausa to the west, the Tuareg and Toubou to the north, the Bulala to the east, and the Sao who were strongly implanted in the Bornu region (and will be decimated by Alooma’s military campaigns). One epic poem extols his victories in 330 wars and more than 1,000 battles. His innovations included the employment of fixed military camps with walls, permanent sieges and scorched earth tactics where soldiers burned everything in their path, armored horses and riders as well as the use of Berber camels, Kotoko boatmen, and iron-helmeted musketeers trained by Ottoman military advisers. His active diplomacy featured relations with Tripoli, Egypt, and the Ottoman Empire, which sent a 200-member ambassadorial party across the desert to Alooma’s court at Ngazargamu. Alooma also signed what was probably the first written treaty or ceasefire in Chadian history.

Alooma introduced a number of legal and administrative reforms based on his religious beliefs and Islamic law. He sponsored the construction of numerous mosques and made a pilgrimage to Mecca, where he arranged for the establishment of a hostel to be used by pilgrims from his empire. As with other dynamic politicians, Alooma’s reformist goals led him to seek loyal and competent advisers and allies, and he frequently relied on eunuchs and slaves who had been educated in noble homes. Alooma regularly sought advice from a council composed of heads of the most important clans. He required major political figures to live at the court, and he reinforced political alliances through appropriate marriages (Alooma himself was the son of a Kanuri father and a Bulala mother).

Kanem-Bornu under Alooma was strong and wealthy. Government revenue came from tribute (or booty if the recalcitrant people had to be conquered) and duties on and participation in trade. His kingdom was central to one of the most convenient routes across the Sahara desert. Many products were sent north, including natron (sodium carbonate), cotton, kola nuts, ivory, ostrich feathers, perfume, wax, and hides, but the most profitable trade was in slaves. Imports included salt, horses, silk, glass, muskets, and copper.

Alooma took a keen interest in trade and other economic matters. He is credited with having cleared the roads, designed better boats for Lake Chad, introduced standard units of measure for grain, and moving farmers into new lands. In addition, he improved the ease and security of transit through the empire with the goal of making it so safe that “a lone woman clad in gold might walk with none to fear but God.” To learn more, check out the books: History of the first twelve years of the reign of Mai Idris Alooma of Bornu (1571-1533) by his Imam: Ahmed ibn Fartua; together with the “Diwan of the sultans of Bornu” and “Girgam” of the Magumi; and The Africans, ed. J.A. Tome 3, 1977.