The great Guadeloupean writer, the Grande dame of Caribbean literature, Maryse Condé has transitioned to the land of our ancestors at the age of 90. Condé’s work has touched so many throughout the world, as it was a bridge between Africa, the Caribbean, and Europe. Her best work, Segu, has been one of my favorites. My first encounter with Maryse Condé’s work, was when I read her book “La Belle Créole.” Then I read Segu, and really that was it! I was sold… It was unforgettable, strong, and vivid. This book might actually be among the first historical fiction books written by a person of African descent on one of the ancient African kingdoms spanning several decades. Set in the 18th century, it followed the life of Dousika Traore, a royal adviser in an ancient historical kingdom based in Segu in modern-day Mali, torn apart by the arrival of the slave trade and Islam. It reminded me of the Alex Haley’s Kunta Kinte or Roots saga. It was deep, rich, and truly captivating.

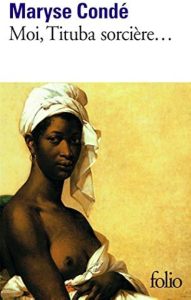

In “I, Tituba: Black Witch of Salem,” Condé told the story of a slave who was one of the first women to be accused of witchcraft during the 1692 Salem witch trials. It was based on the story of an American slave who was tried for witchcraft. Honestly, up until then, I could not fathom that a Black woman could have been on trial back then in the United States; but in reality, given how Africans were uprooted from the continent, and their religion, and spirituality, it should not have come as a surprise.

I read her other book, The last of the African Kings which is a fictional account following King Behanzin’s offsprings and entourage when he was in exile in Martinique, and their lives in the caribbeans and then the United States, after the French deported him there. It skillfully intertwined the themes of exile, memory, hope, loss, with Africa always in the background.

After that, I read her other books A Season in Rihata, The Crossing of the Mangrove, La Vie Scélérate (Tree of Life: A Novel of the Caribbean), Desiderada.

Her themes always embraced motherhood, femininity, race relations, slavery, the Caribbeans, and Africa. Her novels drew upon African and Caribbean history. She has written over 20 novels,

Throughout her life, she was awarded France’s Legion of Honour in 2004, and twice nominated for the International Booker Prize – first for her entire body of work in 2015, then in 2023 for her final novel, The Gospel According to the New World. In 2018, she won an award set up in place of the Nobel Prize in Literature, which was engulfed in scandal. Condé was the first and remains the only winner of the New Academy Prize in Literature, whose judges praised the way she “describes the ravages of colonialism and post-colonial chaos in a language which is both precise and overwhelming“.

The excerpts below are from the Guardian.

=====

… Born Maryse Boucolon in Guadeloupe in 1934, the youngest of eight children, Condé described herself as a “spoilt child … oblivious to the outside world”. Her parents, she told the Guardian, never taught her about slavery and “were convinced France was the best place in the world”. She went to Paris at 16 for her education, but was expelled from school after two years: “When I came to study in France I discovered people’s prejudices. People believed I was inferior just because I was black. I had to prove to them I was gifted and to show to everybody that the colour of my skin didn’t matter – what matters is in your brain and in your heart.”

Studying at the Sorbonne, she began to learn about African history and slavery from fellow students and found sympathy with the Communist movement. She became pregnant after an affair with Haitian activist Jean Dominique. In 1958, she married the Guinean actor Mamadou Condé, a decision she later admitted was a means of regaining status as a black single mother. Within months their relationship was strained, and Condé moved to the Ivory Coast, spending the next decade in various African countries including Guinea, Senegal, Mali and Ghana, mixing with Che Guevera, Malcolm X, Julius Nyerere, Maya Angelou, future Ivory Coast president Laurent Gbagbo and Senegalese film-maker and author Ousmane Sembène.

Unable to speak local languages and presumed to hold francophile sympathies, Condé struggled to find her place in Africa. “I know now just how badly prepared I was to encounter Africa,” she would later say. “I had a very romantic vision, and I just wasn’t prepared, either politically or socially.” She remained outspoken until she was accused of subversive activity in Ghana and deported to London, where she worked as a BBC producer for two years. She eventually returned to France and earned her MA and PhD in comparative literature at Paris-Sorbonne University in 1975.

Her debut novel, Hérémakhonon, was published in 1976, with Condé saying she waited until she was nearly 40 because she “didn’t have confidence in myself and did not dare present my writing to the outside world”. The novel follows a Paris-educated Guadeloupean woman, who realises that her struggle to locate her identity is an internal journey, rather than a geographical one. Condé later recalled the Ghanaian author Ama Ata Aidoo telling her: “Africa … has codes that are easy to understand. It’s because you’re looking for something else … a land that is a foil that would allow you to be what you dream of being. And on that level, nobody can help you.” “I think she may have been right,” Condé later wrote.

… She gained prominence as a contemporary Caribbean writer with her third novel, Segu, in 1984. The novel follows the life of Dousika Traore, a royal adviser in the titular African kingdom in the late-18th century, who must deal with encroaching challenges from religion, colonisation and the slave trade over six decades. It was a bestseller and praised as “the most significant novel about black Africa published in many a year” by the New York Times.