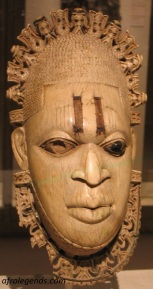

Have you ever stood in front of an African mask and wondered about the artist who made it: what was his name, origin, and life like? A few weeks ago, I had an argument with a European friend who specializes in art history, who tried to convince me, a child of mother Africa, that African art does not have authorship. He claimed that while looking at African masks, they were all cloaked with anonymity, and that probably African art traditions prized anonymity. I had to tell him that he needed to stop looking at African art through his tainted European lenses, but rather try it through African tunnel vision. First of all, African art’s function is not similar to that used by Europeans as decorative art. African art actually has functions that go beyond decorative; the art work has meaning, and a real place in society.

For instance, in the Asante (Ashanti) culture of Ghana, the Akua’ba (Akua’s child) figurines which are among some of the best well-known African wooden figures recognizable by their small disc head lodged on a cylindrical torso with or without arms, were used as legend says by Akua who could not have children; she ordered a figurine which she tied to her back and cared for as instructed by an African traditional priest, eventually being able to conceive; since then, many women desiring children have ordered Akua’ba figurines from artists and gotten them consecrated at shrines, and cared for in hope of conceiving. Also, some of the statues, like fertility statues, serve a particular purpose as the name states.

Anonymity in African art is only a myth invented by Europeans as they came in contact with a foreign culture which they tried to explain via their own tainted cultural glasses. In the case of the Yoruba people of West Africa, as we saw earlier in the naming ceremonies [African Naming Tradition], names given at birth are not just used to differentiate individuals, but also serve to identify the essence of one’s personality and destiny called ori inu (inner spiritual head), which in Yoruba religious belief, determines a person’s success or failure in this world and directs his or her actions. The name also gives information about the person’s family, beliefs, history, origin, and environment. It is sacred! With every naming celebration, there begins a corresponding oriki (citation poetry), which grows with an individual’s accomplishments. Leaders, warriors, diviners, and other important persons, including artists are easily identified by their oriki, which chronicles their achievements [The Griot, the Preserver of African Traditions]. In Yoruba culture, there are different kinds of oriki: oriki Olurun (oriki for God), oriki orisa (oriki for gods/goddesses), oriki Oba ati Ijoye (oriki for monarchs and chiefs), oriki Akinkanju (oriki for warriors), oriki idile (oriki for families), to name just a few.

Below is the part of the oriki of Olowe, one of the greatest traditional Yoruba sculptors of the twentieth century; it was collected by John Pemberton III in 1988 from Oluju-ifun, one of Olowe’s surviving wives, and has been found to be instrumental in reconstructing his life and work. Outstanding Yoruba artists like Olowe whose works have been collected and studied by researchers have been identified in scholarly literature only by their nicknames or bynames such as, Olowe Ise (meaning Olowe from the town of Ise); Ologan Uselu (Ologan from Uselu quarters in Owo); and Baba Roti (father of Rotimi). This was done to protect the artist as he could become a vulnerable target to malevolent forces because of his standing in society or closeness to the king’s court, etc; in that case the artist never revealed his full name to strangers. However, when a person’s oriki is recited, it is assumed that anyone who listens carefully and understands it will know enough about the subject’s identity, name, lineage, occupation, achievements, and other qualities so that stating the person’s given name becomes superfluous. This is found on P. 11 – 12 of A History of Art in Africa, Monica Blackmun Visona, Harry N. Abrams (2001). Thus, authorship in African art is not veiled in anonymity, but rather the way authorship is conceived of is different. Enjoy!

| Olowe, oko mi kare o

Aseri Agbaliju Elemoso Ajuru Agada O sun on tegbetegbe

Elegbe bi oni sa O p’uroko bi oni p’ugba

O m’eo roko daun se…

Ma a sin Olowe Olowe ke e p’uroko

Olowe ke e sona O lo ule Ogoga Odum merin lo se libe O sono un Ku o ba ti de’le Ogoga

Ku o ba ti d’Owo Use oko mi e e libe Ku o ba ti de’kare Use oko mi i libe Ku o ba ti d’Igede

Use oko mi e e libe Ku o ba ti de Ukiti Use oko mi i libe Ku o li Olowe l’Ogbagi L’Use

Use oko mi i libe Ule Deji Oko mi suse libe l’Akure Olowe suse l’Ogotun Ikinniun

Kon gbelo silu Oyibo Owo e o lo mu se |

Olowe, my excellent husband

Outstanding in war. Elemoso (Emissary of the king), One with a mighty sword Handsome among his friends. Outstanding among his peers. One who carves the hard wood of the iroko tree as though it were as soft as a calabash One who achieves fame with the proceeds of his carving … I shall always adore you, Olowe. Olowe, who carves iroko wood. The master carver. He went to the palace of Ogoga And spent four years there. He was carving there. If you visit the Ogoga’s palace, And the one at Owo, The work of my husband is there. If you go to Ikare, The work of my husband is there. Pay a visit to Igede, You will find my husband’s work there. The same thing at Ukiti. His work is there. Mention Olowe’s name at Ogbagi In Use too. My husband’s work can be found In Deji’s palace. My husband worked at Akure. My husband worked at Ogotun. There was a carved lion That was taken to England. With his hands he made it. |