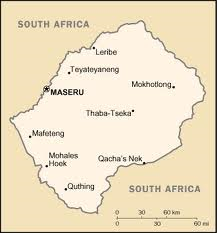

Back in March 2025, the country of Lesotho was suddenly thrown in the spotlight when American President Donald Trump made a dismissive remark during a speech to Congress, saying « nobody has ever heard of » Lesotho while criticizing U.S. foreign aid spending. The comments sparked backlash from Lesotho’s government and prompted many to visit the country, or talk about the country. President Trump was not totally wrong… let’s be honest, before his remark, how many had heard about the country ?… maybe those who visit Afrolegends and who had read about its capital city of Maseru. Unknowingly, President Trump has most likely prompted added tourism to this beautiful landlocked country the size of Belgium entrenched within the country of South Africa.

Today, we will talk about King Moshoeshoe I, the first king of Lesotho.

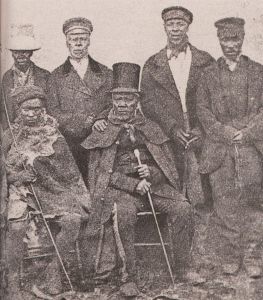

King Moshoeshoe I was the founder and first monarch of Lesotho, known for his diplomatic genius, military leadership, and ability to unite diverse clans into a single nation. He ruled from 1822 until his death in 1870.

King Moshoeshoe I was the first king of Lesotho. At birth, he was named Lepoqo, which means Dispute, because of accusations of witchcraft which were levied on a man in Menkhoaneng around the time of his birth, between 1780 to 1794, where 1786. He was the first son of King Mokhachane, a minor chief of the Bamokoteli sub-clan of the Basotho people and his first wife Kholu, who was the daughter of the Bafokeng clan chief Ntsukunyane. Unlike Shaka Zulu, he had a happy childhood which he always referred to in adult life.

After his initiation ceremony in 1804, he took the name of Letlama, the Binder, and later chose the name Moshoeshoe, a name inspired by the sound of shaving – symbolizing his skill in cattle raids and leadership. It is said that it was chosen after a successful raid in which he had sheared the beards of his victims – the word ‘Moshoeshoe’ representing the sound of the shearing.

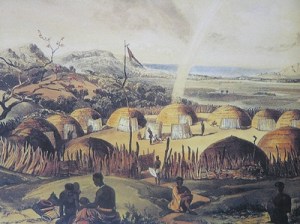

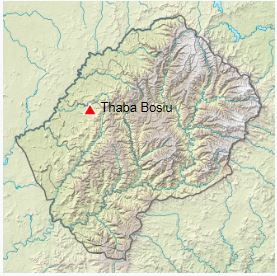

In 1820, Moshoeshoe succeeded his father and formed his own clan and settled at Butha-Buthe Montain, and later moved to the mountain he named Thaba Bosiu or “Mountain at Night” because his people arrived at night, a natural fortress that became the heart of the Basotho Kingdom. Thaba Bosiu served as the capital of the new Basotho nation. One can still find ruins from the 19th century of King Moshoeshoe I’s reign at the top of the mountain; it overlooks iconic Mount Qiloane, an enduring symbol of the nation’s Basotho people.

In 1810, Moshoeshoe married Mamabela, daughter of the Bafokeng chief, Seephephe, who was chosen for him by his father. She became his senior wife assuming the name ’MaMohato (Mother of Mohato – name that she took after the birth of her first son Letsie) with whom he had four sons including Letsie, Molapo, Masopha and Majara as well as a daughter named Mathe. Their relationship was described by visiting British missionaries as deeply affectionate. MaMohato died in 1838. Moshoeshoe practiced polygamy and is known to have had 30 wives in 1833 and close to 140 wives by 1865. After MaMohato, Moshoeshoe considered himself to be a widower. Only the children from his marriage to MaMohato constituted the royal line of descent.

He was known for his generosity toward enemies, often integrating defeated groups into his kingdom. He united various displaced groups during the Mfecane (a period of widespread chaos and warfare in southern Africa), offering protection and forging a strong, centralized state. He also skillfully navigated threats from the Boers, British, and neighboring African groups, often using diplomacy to preserve his people’s autonomy. Due to constant hostilities and encroachments from Boers and wars, he signed an agreement with Queen Victoria of Great Britain to make Basutoland a British protectorate in 1868; the kingdom then became a crown colony in 1884, achieving independence in 1966 at which point the name was changed to Lesotho. Moshoeshoe died on 11 March 1870 and was succeeded by his oldest son Letsie I.

March 11, the day of his death , is celebrated throughout the kingdom as Moshoeshoe Day, a national holiday in Lesotho. The South African-made shweshwe fabric is named for King Moshoeshoe I who once received a gift of it and then popularized it throughout his realm.