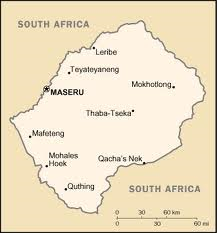

As I see the sale of African lands to multinationals for pennies, or in some cases loans for 20-30-50 years and even 100 years, or like in Kenya (and certainly many other places) for 999 years (Did You Know about the 999-year Lease granted to Europeans in Kenya ?), I cannot help but think of King Moshoeshoe I of Lesotho who, in 1859, prohibited the sale of Sotho land to foreigners. This was a big NO. No ancestral lands could be sold to foreigners. Our current African leaders should learn from our forefathers; they, like Moshoeshoe I of Lesotho, or Gungunyane: the Lion of Gaza or the Last African King of Mozambique, or Mirambo: the Black Napoleon of Tanzania, understood the importance of our lands! The law below also gives a glimpse on the justice system as implemented in the Sotho kingdom under its first king. This is a historical document set in its time to be read with the protection of the integrity and protection of Sotho land in mind.

Below is the access to property law signed by King Moshoeshoe I in 1859 on his homeland of Lesotho. The original can be found in Les Africains, Tome 8, p. 254, ed. Jaguar. Translated to English by Dr. Y., Afrolegends.com

======

Access to property: prohibited for traders, “White or colored”, 1859 law

I, Moshoeshoe, for any trader, whoever he may be, already present in my country, and for anyone who might come to trade with the Basutos ; my word is this :

Trading with me and my tribe is a good thing, and I hope it will grow.

Any merchant who wants to open a shop must first obtain my permission. If he builds a house, I do not give him the right to sell it.

Moreover, I do not give him the freedom to plow fields, but only to cultivate a small vegetable garden.

The merchant who imagines that the place where he stays belongs to him, must abandon this idea, otherwise he will leave; for there is no place on my soil that belongs to the Whites, and I have never given a place to a White, whether verbally or in writing.

Furthermore, any merchant who comes here with a debt, or who contracts one while he is on my soil, whatever his debt may be, if he is brought to me, I will make an inquiry into him in our court of justice in order to be able to settle the matter ; and the debt will be repaid in the way the Basutos repay their debts. But the plaintiff must appear before me, and the debtor as well, so that justice may be done. […]