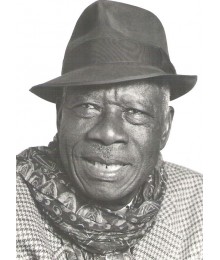

It is with great sadness that I learned of the passing of the great Ivorian writer Bernard Binlin Dadié. Bernard Dadié was a Baobab of African literature, and he was 103 years of age at the time of his passing. On his 100th-year birthday, he had complained of not being able to write as much anymore, given that he still had so much to say! Dadié was a literary virtuoso who brilliantly explored many genres from poetry, to fiction, to theater.

Many have wondered what was the secret of his longevity, and “his children always thought that Dadié was able to surmount all those obstacles and live so long because he was deeply in love with his wife,” said Serge Bilé [« Ses enfants ont toujours pensé qu’il a pu traverser toutes ces épreuves et vivre si longtemps car il était amoureux de sa femme » Jeune Afrique] writer, journalist, and whose mother was a cousin of Assamala Dadié (Dadié’s wife).

Dadié was born in Assinie, Côte d’Ivoire, and attended the local Catholic school in Grand Bassam and then the Ecole William Ponty. He worked for the French government in Dakar, Senegal. Upon returning to his homeland in 1947, he became part of its movement for independence: he denounced colonialism and neo-colonialism. Before Côte d’Ivoire‘s independence in 1960, he was detained for sixteen months for taking part in demonstrations that opposed the French colonial government.

Climbié, his most well-known novel was published in 1956, and was the first Ivorian fiction. With his theater piece The cities (Les Villes), played in Abidjan in April 1934, Dadié gave Francophone Africa its first drama piece. I am sure there were others played in the olden ancestral days, but this was the first one written in Molière’s language. He was also the first to win the great literary price of Black Africa (le grand prix littéraire de l’Afrique noire) twice in 1965 with Boss of New York (Patron de New York, Présence Africaine, 1964), and The City where No One Dies (La Ville où nul ne meurt, Présence Africaine, 1969) in 1968. His other big novels are: Le Pagne noir – Contes africains (1955), Un Nègre à Paris (Présence Africaine, 1959), Les voix dans le vent (1970), Monsieur Thôgô-Gnini (1970) ou les poèmes du recueil La rondes des jours (1956). In recent years, his poem “Dry Your Tears Afrika” (“Seche Tes Pleurs” de Bernard Binlin Dadié / “Dry your Tears Afrika” by Bernard B. Dadié) was set to music by American composer John Williams for the Steven Spielberg movie Amistad. Lastly, a street bears his name in Abidjan.

Among many other senior positions, starting in 1957, he held the post of Minister of Culture in the government of Côte d’Ivoire from 1977 to 1986. As a twist on fate, next week will come out in Côte d’Ivoire, a book titled 100 writers pay tribute to Dadié (100 écrivains rendent hommage à Dadié) in the Éburnie éditions. Bernard Dadié is the symbol of Côte d’Ivoire‘s deep and rich culture, marking a literary resistance to colonialism and neo-colonialism, and a strong love for his people, continent, and race.

I live you here with the link to his poem “I Thank you God” which we had published a while back: “Je vous Remercie Mon Dieu” de Bernard B. Dadie / “I Thank You God” from Bernard Binlin Dadie. Yes, we thank God for his son Bernard Dadié who has graced this earth and shown us the way, revived our pride, and dried our tears (“Seche Tes Pleurs” de Bernard Binlin Dadié / “Dry your Tears Afrika” by Bernard B. Dadié). I would like to tell all those who mourn him, that the fierce spirit of Bernard Dadié lives on, and we are his legacy which we should uphold.

“We cannot hurt ourselves just for the sake of it. When you hurt somebody you hurt yourself. Down the line, the ripple of it comes back to you.”

“We cannot hurt ourselves just for the sake of it. When you hurt somebody you hurt yourself. Down the line, the ripple of it comes back to you.”