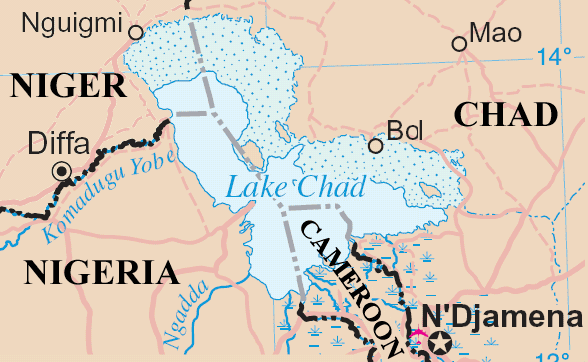

In the past, we have talked about the great Ghana Empire of West Africa whose main center of trade was Koumbi Saleh, and whose economy was based around gold, salt, copper, and other goods. The imports included textiles, ornaments, and other materials. Many of the handcrafted leather goods found in old Morocco also had their origins in the Ghana Empire. Several strong cities of the Ghana Empire are today on the UNESCO World Heritage List, such as Koumbi Saleh, Ouadane, Chinguetti,or Oualata. The historian and scholar Ibn Battuta visited Oualata in 1352, and gives an amazing report of the people of Oualata (Walata). Enjoy! These can be found in the Travels of Ibn Battuta called A Gift to Those Who Contemplate the Wonders of Cities and the Marvels of Traveling, better known as the Rihla (or “travels”). In Oualata, Ibn Battuta mentions his amazement that the society is matrilineal which he had not seen before anywhere in the world except among Indians of Malabar, and notices the importance of women in the society, and how they are well-treated, and mutual respect between men and women. A lot of these traditions are still be observed throughout Africa today.

=====

My stay at Iwalatan [Walata] lasted about fifty days; and I was shown honour and entertained by its inhabitants. It is an excessively hot place, and boasts a few small date-palms, in the shade of which they sow watermelons. Its water comes from underground waterbeds at that point, and there is plenty of mutton to be had. The garments of its inhabitants, most of whom belong to the Massufa tribe, are of fine Egyptian fabrics.

Their women are of surpassing beauty, and are shown more respect than the men. The state of affairs amongst these people is indeed extraordinary. Their men show no signs of jealousy whatever; no one claims descent from his father, but on the contrary from his mother’s brother. A person’s heirs are his sister’s sons, not his own sons. This is a thing which I have seen nowhere in the world except among the Indians of Malabar. But those are heathens; these people are Muslims, punctilious in observing the hours of prayer, studying books of law, and memorizing the Koran. Yet their women show no bashfulness before men and do not veil themselves, though they are assiduous in attending the prayers. Any man who wishes to marry one of them may do so, but they do not travel with their husbands, and even if one desired to do so her family would not allow her to go.

The women there have “friends” and “companions” amongst the men outside their own families, and the men in the same way have “companions” amongst the women of other families. A man may go into his house and find his wife entertaining her “companion” but he takes no objection to it. One day at Iwalatan I went into the qadi’s house, after asking his permission to enter, and found with him a young woman of remarkable beauty. When I saw her I was shocked and turned to go out, but she laughed at me, instead of being overcome by shame, and the qadi said to me “Why are you going out? She is my companion.” I was amazed at their conduct, for he was a theologian and a pilgrim [to Mecca] to boot. I was told that he had asked the sultan’s permission to make the pilgrimage that year with his “companion”–whether this one or not I cannot say–but the sultan would not grant it.