Fenus unciarum refers to an ancient Roman concept of interest on loans. The term “unciarum” comes from the latin “uncia,” which means “twelfth,” and “fenus” means interest. Essentially, it was a legal term used to describe the interest rate of 1/12 (or about 8.33%) per month, which translates to an annual interest rate of approximately 100%. The Twelve Tables, an early Roman legal code, established this rate to protect borrowers from exorbitant interest rates. This was a common practice in Roman law which was applied in Africa during the slave trade. The debtor who cannot redeem himself becomes a slave: he can redeem himself by selling his son to the creditor. According to the law of the XII tables, the creditor can sell the debtor beyond the Tiber.

The fidelity of this scheme in Black Africa under the slave system is corroborated by Mungo Park, the Scottish explorer who visited West Africa in the 1790s. After an exploration of the upper Niger River around 1796, he wrote a popular and influential travel book titled Travels in the Interior Districts of Africa in which he theorized the Niger and Congo merged to become the same river, though it was later proven that they are different rivers. In this book, he shed a light also on the fenus unciarum use in Africa.

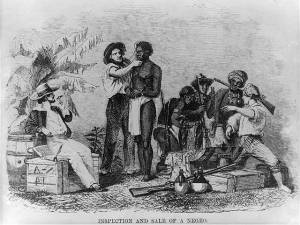

“When a Negro takes goods on credit from Europeans on the coast and does not pay at the agreed time, the creditor has the right, according to the laws of the country, to seize the debtor or, if he cannot find him, someone from his family, or finally, as a last resort, someone from the same kingdom. The person thus seized is detained while his friends are sent to search for the debtor. When the latter is found, an assembly of the chiefs of the place is called, and the debtor is forced, by paying his debt, to release his relative. If he cannot do this, he is immediately seized: he is sent to the coast, and the other is set free. If the debtor is not found, the arrested person is obliged to pay double the amount of the debt, or he himself is sold as a slave…”

From this, one can easily see how an entire kingdom could be captured.