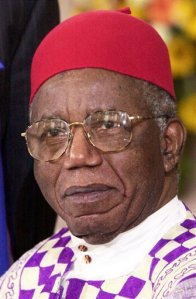

World acclaimed Kenyan writer Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o is no longer. Millions of school children in Africa grew up reading his first books Weep not child (1964), the first novel in English published by an East African, followed by The river between (1965) and A Grain of Wheat (1967). A Cameroonian friend of mine used to love reading The river between, and could recite almost every line. Weep not child explored the impact of the Mau Mau rebellion on a young boy’s family and education, The river between focused on the cultural clash between traditional Gikuyu society, while A Grain of Wheat focused on the disillusionment of the post-independence era.

Like the venerated Chinua Achebe, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o was counted among the baobabs of modern African literature, as the author of several novels, plays, short stories, critical pieces, and children books. Like Achebe, he was tipped several times to win the Nobel Prize for Literature, leaving fans dismayed each time the medal slipped through his fingers. We are counted among those fans who each time hoped, but were always disappointed… it’s like the real African authors never get rewarded. This is a lesson for all that we need to reward our own, create awards and celebrate our own, instead of waiting for others to celebrate them. His daughter Wanjiku wa Ngũgĩ who announced his passing on May 28, 2025, said, “He lived a full life, fought a good fight. As was his last wish, let’s celebrate his life and his work.”

Ngũgĩ reached fame writing in English, and then decided to write in Gikuyu, his mother-tongue. Today, his books are written in Gikuyu, and then translated into English; he was a strong proponent of African languages and was adamant about expressing his art in Gikuyu. Like so many East African leaders, he attended the prestigious Makerere University in Uganda, and later the University of Leeds in the UK. Upon his return to Kenya, he taught at the University of Nairobi where he worked to “decolonize the minds,” campaigning to decolonize the curriculum by prioritizing African literature and languages. He was instrumental in the abolition of the English Literature Department in favor of a broader, African-centered literary program. The 1970s decade also saw him drop his patronym James Ngugi, to be fully known as Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o.

His work spanned over six decades, documenting the transformation of his country, Kenya, from a colony of Great Britain to a democracy with all its issues. He fought the government and was arrested several times, and spent a year at a maximum security prison where he wrote his novel Devil on the Cross (Caitaani mũtharaba-Inĩ), the first modern novel in Gikuyu, written on prison toilet paper. Once out of prison, faced with constant harassment from the government, he went into exile and taught at some of the world’s best universities, including Yale University, New York University, Northwestern University, and the University of California, Irvine where he was a Distinguished Professor of English and Comparative Literature and served as first director of the International Center for Writing and Translation.

His was a unique voice, a voice which never stopped to urge for the decolonization of the minds. To this effect, he wrote Decolonising the Mind: The Politics of Language in African Literature (1986) which advocates for linguistic decolonization of Africa; the book became one of his best known non-fiction work. In his speech at Wits University in Johannesburg in 2017, titled ‘Secure the base, decolonise the mind’, Ngũgĩ spoke about the ‘power relationship between the language of the conqueror and the language of the vanquished’, and asked whether, after fifty years, we have ‘regained the cultural and intellectual independence that we had lost to colonialism’, adding ‘I have always argued that each language, big or small, has its unique musicality; there is no language, whose musicality and cognitive potential, is inherently better than another,’ he said [The Johannesburg Review of Books]. Ngũgĩ is survived by 9 children of whom 4 are also authors like himself.

To learn more, please check out The Johannesburg Review of Books, Nyakundi Report, Pulse Kenya, and the BBC. So long to our Kenyan giant of literature… we will not weep, but keep celebrating Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o ‘s life!