Last week, the Victoria & Albert Museum (V&A) and the British Museum “returned” some artifacts looted from the Ashanti Kingdom in modern-day Ghana, after over 150 years. When one reads the headlines in the news, one can only clap, until learning that this is a “long-term loan“! Wait! What? About 32 gold and silver items which had been stolen from the court of the Asantehene (Asante king) in the 19th century, have been sent on a long-term loan back to the Asante court. First, how long is a “long-term loan”? Second, why is it a loan, when these objects were looted from the Asantehene’s court back in the 19th century? They were not gifted, they were not sold, they were STOLEN! And to top it off, there has been a chief negotiator on the Ghanaian side to ensure that the objects will be in safe hands in Ghana! What? So, these objects do not belong to Ghanaians, and if something were to happen to these Ghanaian objects that were stolen by the British but are now hosted in British museums while on Ghanaian soil on long-term loan, then one can only bet that the British would make the Ghanaians pay for something that is theirs! Which world are we living in? Knowing the treacherous nature of these people, who is to say that they will not orchestrate a new theft of these objects so as to further deepen the debts under which Ghanaians are already crumbling? Actually, long-term in this case means 3 years, with the option of renewing for 3 years! This loan is probably not even free! Why, oh why, do we, Africans, agree to such deals?

Read for yourself… excerpts from the BBC

=====

The UK has returned [how can it be called return when it is a loan?] dozens of artefacts looted from what is today Ghana – more than 150 years after they were taken [i.e. stolen].

Some 32 gold and silver items have been sent on long-term loan to the country by the Victoria & Albert Museum (V&A) and the British Museum.

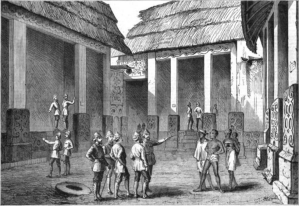

They were stolen from the court of the Asante king, known as the Asantehene, during 19th century conflicts between the British and powerful Asante people.

The objects are expected to be returned [loaned – see how the writer of this piece wants to create confusion in our minds?] to the current king on Friday.

His chief negotiator, Ivor Agyeman-Duah, told the BBC that the objects are currently in “safe hands” in Ghana ahead of them being formally received. They are due to go on display next month at the Manhyia Palace Museum in Kumasi, the capital of the Ashanti region, as part of celebrations to mark the silver jubilee of the current Asante King Otumfuo Osei Tutu II.

… Among the returned artefacts are a gold peace pipe, a sword of state and gold badges worn by officials charged with cleansing the soul of the king. The gold artefacts are the ultimate symbol of the Asante royal government and are believed to be invested with the spirits of former Asante kings.

The Asante people built what was once one of the most powerful and formidable states in west Africa – trading in, among others, gold, textiles and enslaved people. The kingdom was famed for its military might and wealth.