I couldn’t pass on the opportunity to share this picture of a beautiful hibiscus flower. The colors were very vibrant, and the mixture of the yellow, orange, white, purple, and red, all blended in perfect harmony. There is so much peace emanating from it. This is part of all the beauty that the natural world has to offer in Africa, and around the globe. May your day be just as harmonious as the colors on this flower. Enjoy!

Category: Great Art

A Heritage of Art on the African continent

Omar Victor Diop and Project Diaspora

I was impressed by photographer Omar Victor Diop‘s latest work. His Project Diaspora is a self-portrait mimic of original paintings of notable African men in European history, while using football equipment as props. With this work, Diop tries to explore his own development as an artist, but also to rectify misconceptions of an all-white Europe by highlighting accurate African presence in Europe in the 15th through 19th century. Thereby demonstrating that Africans in Europe in the 15-19th centuries were not only slaves, but also noblemen, as seen on real paintings he found in museums and archives across Europe!

See how our views have been distorted for so long? It means that from 1400s until 1800s there were African noblemen, generals, etc (like the Ghanaian professor in Germany Anton-Wilhelm Amo in the 1700s, or General Gannibal the grandfather of the celebrated Russian poet Alexander Pushkin) in Europe! Imagine that! Africans were not just slaves, but noblemen, and much more! I simply love it. Please people, take a look at Omar Victor Diop’s Project Diaspora, his website omarviktor.com, and this article on Okayafrica.com and rediscover some history through his modern depictions of the past.

Happy Holiday Season 2014

I just wanted to wish you all a Happy holiday season 2014. Merry Christmas and Happy new year. May this holiday season be full of joy, happiness, abundance, and blessings. Enjoy the picture below as a present from Dr. Y., Afrolegends.com, for a happy holiday season.

The Nguon Festival: A Bamun Tradition Dating back Centuries

Last month, the Nguon festival took place in Foumban (also spelled Fumban), in the Noun region of Cameroon, celebrating its 545th edition. So what is this centuries’ old tradition called the Nguon?

Celebrated every two years by the Bamoun people (also spelled Bamun, Bamoum, Bamum) of the Noun region of Cameroon, the Nguon festival is over 600 years old. It is a true display of the rich culture and tradition of the Bamoun people. The Nguon festivities are spread over 7 days, with each day marked by several activities such as traditional dances, ritual ceremonies, conferences, and great food showcasing the richness of the Bamoun culture.

During the Nguon, the Bamoun people gather to express their ideas and grievances. The pinnacle of the festivities occurs when the King is deposed, judged on his governance and achievements for the last two years and eventually reinstated. Talk about an example of democracy! The Nguon thus allows the king to connect with his people; it is a time when the distinctions and hereditary privilege classes cease to exist.

So why the name Nguon, you might ask? Well, the Nguon is the name of a species of locust whose large presence in the fields announced the period of harvest of millet, maize and other cereals. It is a celebration of the harvest, of good times. That is the reason why this centuries’ old festival was always held during the harvest period, usually in late July, or early August. In the old days, it was celebrated once a year, but since 1996, it has become a biennial celebration. On the first day of the celebration, all the lights at the King’s palace are turned off. Slowly, the owners of the Nguon enter into the royal court, in total darkness accompanied by the sound of drums, giving it a mystical touch.

It was all started in 1394 by Nchare Yen, the founder of the Bamoun kingdom (this will be for another day). After Nchare Yen established his kingdom on the shores of the Noun River, he befriended Mfo Mokup, a neighboring king who had a secret society called Nguon, which ensured the supply and equitable distribution of food across his kingdom (like Joseph in Egypt in the Bible). Every year, during the harvest period, the Nguon owners (members of the secret society) roamed the village to ensure that villagers brought their harvest to the king’s palace; in turn, the king redistributed the products of the harvest to all his subjects across the kingdom. Any surplus was stored in an attic in preparation for hard times. The gathering ended in 3 days of celebration known as the Nguon festival.

Upon seeing this, King Nchare Yen adopted this governing method whereby Nguon owners would not only travel throughout the kingdom to ensure good food supply, but would also gather all of the people’s grievances, and detect abuses committed in the name of the King. Their responsibility was thus to keep the king aware of any problems, and in touch with his constituency. During colonial times, the French did not appreciate this way of governing, as it gave too much power to the local King; so they banned the Nguon in 1924 after deposing Sultan Njoya. It was fully restored by his successor Sultan Njimoluh Njoya after Cameroon’s independence. Since 1996, the current monarch, Sultan Ibrahim Mbombo Njoya, has made it a biennial celebration, and transformed it into an international event attracting tourists from around the world.

According to His Majesty Sultan Ibrahim Mbombo Njoya the Nguon is the “cultural identity of the Bamoum”. It is a celebration of the people’s warmth, and joy at sharing their cultural heritage. It is extremely beautiful to see people celebrate their culture that way, dressed in full attire: the warriors demonstrating their skills, reenacting centuries’ old traditions, telling centuries’ old stories, great music, great dancers, delicious food, the women dressed like true African queens, and the euphoric ambiance. The blog My African Chronicles has great pictures of the event two years ago.

Adinkra Symbols and the Rich Akan Culture

Today, we will talk about Adinkra symbols of the Akan people of Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana.

The Adinkra symbols are believed to originate in Gyaman, a former kingdom in modern day Côte d’Ivoire. According to an Ashanti (Asante) legend, Adinkra was the name of a king of the Gyaman kingdom, Nana Kofi Adinkra. King Adinkra was defeated and captured in a battle. According to the legend, Nana Adinkra wore patterned cloth, which was interpreted as a way of expressing his sorrow on being taken to Kumasi, the capital of Asante. He was finally killed and his territory was annexed to the kingdom of Asante. The Asante people, around the 19th century, took to painting of traditional symbols of the Gyamans onto cloth, a tradition which has remained to this day.

The arrival of the adinkra in Akan culture seems to date as far back as 1817, when the English T.E. Bowdich collected a piece of adinkra cotton cloth from the city of Kumasi. The patterns on it were printed using carved calabash stamps and a vegetable-based dye. The cloth featured fifteen stamped symbols, including nsroma (stars), dono ntoasuo (double Dono drums), and diamonds, and is currently hosted at the British Museum in London.

Adinkra symbols are visual representation of concepts and aphorism developed by the Akan people of Ghana. Adinkra symbols are extensively used in fabrics, pottery, logos, and advertising. They can also be found on architectural buildings, as well as on traditional Akan gold weights, and sculptures as well as stools used for traditional rituals. The adinkra symbols are not just decorative objects, or drawings, but actual messages conveying ancient traditional wisdom relevant to aspects of life or the environment. A lot of the Adinkra symbols have meanings linked to proverbs, such as the sankofa symbol. Sankofa, in the Twi language, translates in English to ” reach back and get it” (san – to return; ko – to go; fa – to look, to seek and take) or the Adinkra symbol of a bird with its head turned backwards taking an egg off its back, or of a stylised heart shape. It is often associated with the proverb, “Se wo were fi na wosankofa a yenkyi,” which translates “It is not wrong to go back for that which you have forgotten.” Other Adinkra symbols depict historical events, human behavior and attitudes, animal behavior, plant life, and objects’ shapes.

Adinkra means ‘goodbye’ or ‘farewell’ in the Twi language of the Akan ethnic group, to which the Asante belong. No wonder the Akan people, and particularly the Asante, wore clothes decorated with Adinkra symbols mostly for funerals as a way to show their sorrow, and to bid farewell to the deceased.

Adinkra cloths were traditionally only worn by royalty and spiritual leaders for funerals and special occasions. They were also hand printed on undyed, red, dark brown, or black hand-woven cotton fabric depending on the occasion and the wearer’s status. Today, adinkra is worn by anyone, women, men or children, and it is frequently mass-produced on brighter colored fabrics. The 3 most important funerary Adinkra are: the dark – brown (kuntunkuni), the brick – red (kobene), and the black (brisi). There are however, other forms of which cannot be properly called mourning cloth. Their bright and light backgrounds classify them as Kwasiada Adinkra or Sunday Adinkra meaning fancy clothes which cannot be suitable for funerary contents but appropriate for most festive occasions or even daily wear.

The center of traditional production of adinkra cloth is Ntonso, 20 km northwest of Kumasi, the city where the Englishman was first given it in 1817. Dark Adinkra aduro pigment for the stamping is made in Ntonso, by soaking, pulverizing, and boiling the inner bark and roots of the badie tree (Bridelia ferruginea) in water over a wood fire. Once the dark color is released, the mixture is strained, and then boiled for several more hours until it thickens. The stamps are carved out of the bottom of a calabash piece, and measure on average 5 to 8 cm2.

Enjoy the video below on Adinkra, and the articles on Adinkra symbols, Adinkra in Ntonso and the article on The 21st Century Voices of the Ashanti Adinkra and Kente Cloths of Ghana with gorgeous images of the process of making Adinkra stamps and clothes, and lastly GhanaCulture.

Habib Benglia and French Theater

Today, I would like to talk about Habib Benglia, one of the pioneers of Black theater and cinema in France.

Habib Benglia was an African artist born in Oran, Algeria, on 25 August 1895. He was originally from Mali, and lived in Timbuktu throughout his childhood. He then moved to France for studies. After high school, he wanted to become an agricultural engineer. However, one evening in 1913, at the Café Riche, while describing his love for theater and having fun with his friends reciting prose, he was noticed by Régine Flory who presented him to Cora Lapercie. That same year, she made him star at the Renaissance in Le Minaret of Jacques Richepin, then he went on to play in Aphrodite by Pierre Frondaie, and L’Homme riche of Jean-José Frappa and Dupuy-Mazuel.

The first world war of 1914 started, and Benglia joined the French troops as many other skirmishers (tirailleurs). Demobilized just before the end of the war, he resumed theater with Firmin Gémier, in L’Oedipe Roi de Bouhélier. In 1923, he became the first black actor to star in the main role at the national French theater at the age of 27: it was in The Emperor Jones whom Gaston Baty put in scene at the Odéon. Benglia always dreamt of seeing Black theater unveiled in France, which would reveal evidence of an African/Black art. He also wrote a few plays: one of them, Un soir à Bamako (An evening in Bamako) was broadcasted in 1950. He passed away in 1960 after having starred in over hundreds of plays.

Benglia was a versatile and prolific actor, who was confined to secondary and codified roles in colonial cinema, and as a result was largely ignored by critics. This was both the fate of many actors (particularly Black actors in his time), overshadowed by stars, and the result of prejudice and racism. Benglia’s roles were always very traditional. Colonial cinema, both as propaganda or exotic entertainment, made proficient use of his abilities. Originally a conveyor of stereotypes, this genre gradually evolved toward more truth and realism, but never gave Benglia the opportunity to rise to stardom. A few plays where Benglia held the main role was Dainah la Métisse, then Sola, and Les Mystères de Paris, as well as in les Enfants du Paradis.

Black Fashion Week in Paris, 2013

Last week was the second edition of ‘Black Fashion week in Paris’, a fashion show where African stylists and designers, and those of the African diaspora expose their work. The Fashion show was held a few meters from the Chanel and Ritz houses, and was organized by the Senegalese stylist Adama Paris who perpetuated the work done by Alphadi with the FIMA (Festival International de la Mode Africaine). 16 stylists of African descent presented their work, ranging from the maestro himself, Alphadi, to Adama Paris, to the Cameroonian Martial Tapolo, to the Haitian Zacometi (who specializes in men’s fashion only), to the Malian Mariah Bocoum, or to the Malagasy Eric Raisina, etc. This was a golden opportunity to discover new talents, and introduce their styles to the global scene, from Dakar to Antananarivo, and hopefully to shops in Los Angeles, and Paris. It was pure beauty, and I wanted you to check out the RFI diaporama on Black Fashion Week 2013. Don’t forget to check out the website of Black Fashion Week Paris. Enjoy the new era of African stylists who are introducing styles just as hip as Chanel and Dior. Below is a video of the first edition: Black Fashion Week 2012.

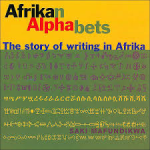

African Alphabets: Ancient Writing in Africa

I always thought that the Egyptian hieroglyphs or the yet undeciphered Meroitic alphabet were not the only signs of ancient writing in Africa. I also always thought that there were other forms of writing throughout Africa, and not just in the northern part. So I was happy to hear Saki Mafundikwa, the founder of Zimbabwe‘s first graphic design school and new media, talk about his book Afrikan Alphabets: The Story of Writing in Afrika, which is a comprehensive review of African writing systems throughout centuries. Mafundikwa left a very successful career in New York to return to his home country and open this school, so as to inspire the newer generations of African designers to look inward (to their own rich cultures) as opposed to outward (toward Europe) as they have done in the past decades. He sums it up so well in his favorite Ghanaian glyph, Sankofa, which means “return and get it” — or “learn from the past.” It is refreshing to learn about these systems, from simple alphabets to secret symbols, from the Adinkra of Ghana, to Mende, Vai, Nsibidi, Bamum, Somali, and Ethiopian scripts which date back centuries.

It is above all refreshing to realize that Africans have their own way of thinking which can be perceived in their designs, and that ultimately graphic designs date as far back as the ancient Egyptians and can be observed throughout Africa. Take the time to read Saki Mafundikwa in his own words. Enjoy Saki Mafundikwa’s speech at one of the TED conference.

Kofi Awoonor: Celebrating the Life of Ghanaian Poet

Today, I would like to talk about the legendary Ghanaian poet, writer, and diplomat Kofi Awoonor who lost his life this past weekend during the shootings at the Westgate Mall in Nairobi, Kenya.

Well, many articles would tell you all about this man who was born George Kofi Nyidevu Awoonor-Williams, but who will end up using Kofi Awoonor as his pen name. Kofi Awoonor was a poet whose poetry was based on Ewe / Ghanaian mythology and imagery. His writings include the oral traditions of African village songs, with their various communal forms, themes, and functions/ceremonies. For instance, his poem ‘The Purification’ records a sacrifice to the sea-god in a time of poor fishing. One can find a sense of melancholy in his writings. Enjoy this snippet from one of his poem ‘Songs of Sorrow.’ To learn more about this man, check this very good article on The Guardian, the BBC, and don’t forget to go to The Poetry Foundation of Ghana to read the end of this poem and other pieces by him.

Songs of Sorrow

I

Dzogbese Lisa has treated me thus

It has led me among the sharps of the forest

Returning is not possible

And going forward is a great difficulty

The affairs of this world are like the chameleon faeces

Into which I have stepped

When I clean it cannot go.

I am on the world’s extreme corner,

I am not sitting in the row with the eminent

But those who are lucky

Sit in the middle and forget

I am on the world’s extreme corner

I can only go beyond and forget.

My people, I have been somewhere

If I turn here, the rain beats me

If I turn there the sun burns me

The firewood of this world

Is for only those who can take heart

That is why not all can gather it.

The world is not good for anybody

But you are so happy with your fate;

Alas! the travelers are back

All covered with debt.

…

By Kofi Awoonor

Commemorating Agostinho Neto’s life – Angola’s National Heroes Day

Today is Angola’s National Heroes’ Day commemorating Angolan heroes, and is a celebration of the life of one of their heroes, President Agostinho Neto who was born on this special day. To mark this day, and to celebrate in style, I propose yet another poem from Angola’s greatest poet, President Neto himself. Enjoy! (I translated from Portuguese to English so it might not be the greatest… if you have a better translation, feel free to share).

Noite by Agostinho Neto – Translation by Dr. Y., Afrolegends.com

| Noite

Eu vivo Vou pelas ruas São bairros de escravos Onde as vontades se diluíram Ando aos trambolhões Também a noite é escura. |

Night

I live in the dark quarters of the world without light and life. I fumbled through the streets leaning on my dreams stumbling on slavery to my desire to be. Slave quarters worlds of misery dark quarters. Where the wills were diluted and the men were confused with things. I walk in unknown streets without tripping Streets soaked in with mystical light and the terror arm of ghosts. The night is also dark. |